In order to achieve long-term energy supply goals, the Indian government has renewed its emphasis on affordability, sustainability, lower emissions and security of energy, drawing attention towards renewable energy sources and natural gas. The government, through its initiatives, has indicated its will to make India a gas-based economy by boosting domestic production and buying cheap liquefied natural gas (LNG). It has set an audacious target to raise the share of gas in its primary energy mix from 6 per cent to 15 per cent by 2022 through gas market development, infrastructure development, demand/supply balancing, policy streamlining, etc.

Vision 2030 Natural Gas Infrastructure Document

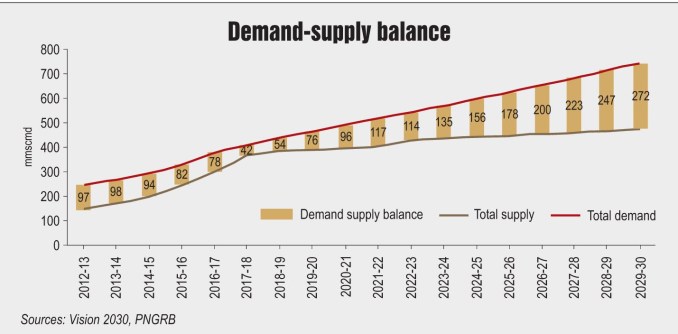

The Petroleum and Natural Gas Regulatory Board (PNGRB) in 2013 came up with a vision document for a gas-based economy, which was to act as a guiding tool for infrastructure development, keeping in mind the demand and supply balance (see Figure).

None of these demand/supply figures were met during the period 2013-18 and the target of making gas account for 20 per cent of the energy mix by 2030 seems impossible due to the lack of concrete measures. The Vision 2030 plan had assumed a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.8 per cent for the demand of natural gas, which was heavily constrained due to the lack of a supporting policy framework to augment gas consumption and gas infrastructure.

Challenges of a gas-based economy

In order to raise the share of gas in the primary energy mix, the gas consumption must reach the level of ~160 bcm and production should reach ~40 bcm by 2022, from the present ~52 bcm and ~32 bcm respectively (BP Energy Outlook 2018 Extrapolation). LNG imports/gas supplies through the Transnational Gas Pipeline will primarily meet the shortfall due to low gas production. It will be difficult to achieve these projections due to the following challenges:

LNG import terminal

India imports around 50 per cent of natural gas (around 26.33 bcm in the last year). The growth in natural gas infrastructure has been around the developed gas fields or LNG import terminals. Gujarat and Maharashtra being close to the source of supply consume more than 50 per cent of the gas. The gas infrastructure in these states is among the best in India.

In order to improve the per capita consumption of natural gas in India and optimise the transportation of natural gas, a well distributed network of LNG terminals both across the eastern side and western side is required. The development of LNG terminals till now has been concentrated in Gujarat because of infrastructure availability. The state has achieved a 24 per cent gas contribution in its primary energy mix.

India needs around 90 million metric tonnes per annum (mmtpa) (120 bcm) of operational capacity widely distributed across the demand centres along the east and west coast of India. This will translate into an installed capacity of around 100 mmtpa considering a capacity utilisation of 90 per cent for each plant, which is very high considering the world average of 50-60 per cent capacity utilisation.

India has four LNG re-gasification terminals: Dahej (10 mmtpa), Hazira (5 mmtpa), Dabhol (5 mmtpa) and Kochi (5 mmtpa), all located on the west coast. Dabhol has been unable to operate at high capacity due to the prolonged lack of a breakwater facility, and Kochi has had a low utilisation rate as a result of long delays in being connected to the regional markets.

India currently has an installed capacity of 30 mmtpa and a planned capacity of around 20 mmtpa is likely to come up by 2022. This leaves us with a shortfall of around 50 mmtpa to achieve the target of primary energy mix for gas. This additional capacity requires an investment of $10 billion-$15 billion in just LNG import terminals. As the concept-to-commissioning process for an LNG import terminal takes around five years, it seems improbable that the target of 15 per cent gas in the Indian primary energy can be achieved by 2022. However, a floating system like FSRU, FSU+FRU, FSU+ onshore/jetty re-gasification, etc. may be utilised for a shorter implementation cycle.

Pipeline network

Pipeline network

Since the NGG was conceptualised in 2000, India has built more than 16,470 km of gas pipeline network with a design capacity of approximately 384 million cubic metres (mcm) per day. However, the pipeline network has been developed mostly in the northern and western regions. A large part of the country lacks transmission infrastructure and access to gas. NGG is a prerequisite for a gas-based economy and it should be connected to all the primary gas supply sources/LNG import terminals and all prospective demand centres such as the industrial cluster, big cities, etc.

There are two main bottlenecks for pipeline network development: first, infrastructure is not being built quickly enough to support demand in the growing regional markets and second, parts of the existing infrastructure remain underutilised. There are also regional imbalances: 40 per cent of infrastructure is concentrated in two western states (Gujarat and Maharashtra), whereas five north-eastern states, and the eastern, southern and central regions have limited or no pipeline infrastructure. In comparison, India’s gas reserves are largely located in the eastern and western offshore basins, and onshore in the north-eastern states. As of September 2016, the average pipeline capacity utilisation was 40 per cent. Three main factors have impeded the progress of gas infrastructure:

- Infrastructure companies have been hesitant to lay pipelines without an anchor consumer in place. At the same time, anchor consumers (such as fertiliser plants) are reluctant to contract future offtake because of the delays in infrastructure development. This has occurred in the past, partially due to misallocation under the gas utilisation policy.

- Companies utilise a legislative provision called the “right to use” land, where land is temporarily acquired (without ownership) for laying pipelines after due compensation to landowners. This has met with public protests and litigation for land acquisition; a case in point being GAIL’s pipeline to connect the Kochi re-gasification terminal to Tamil Nadu.

- There is lack of clarity around the downstream regulatory framework. The PNGRB is the downstream regulator, but has on occasions been superseded by the federal government on pipeline network decisions.

City gas is a relatively new and expanding sector, primarily limited to the urban areas. Households and the transport segment across the country are top priority customers and the government is meeting 100 per cent of their gas requirement through domestically produced gas. Guidelines in this regard were issued in February 2014. Unfortunately, efforts towards the auctioning of new areas for city gas distribution (CGD) development became successful only in 2018 and, therefore, its development along with complementary gas pipeline support may bring in fruits only post 2022.

Domestic gas

Domestic gas production is stagnant as the result of new policies like Hydrocarbon Exploration and Licensing Policy/Open Acreage Licensing Policy shall be known only after a few years. However, the CBM policy, which has a market-driven pricing mechanism, may help in gas production in a limited manner. Domestic gas production is expected to grow at a CAGR of 2.9 per cent (BP Energy Outlook 2018) and hence, in all likelihood, the gap in supply and demand will increase further.

Transnational pipeline

The government is also considering regional pipelines that would rely on gas from the neighbouring countries to increase supplies like the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India Pipeline (TAPI). When completed, the pipeline will be able to transport roughly 30 mmscmd. Another pipeline project, the Middle East to India Deepwater Pipeline (MEIDP)/South Asia Gas Enterprise subsea pipeline (SAGE), will supply Iranian gas to the Indian market by bypassing the Pakistani land route across the Arabian Sea. The proposed project will have a capacity of 31.1 mmscmd per pipeline, and has been noted as the only trans-national gas pipeline currently feasible outside of all conflict zones.

A third pipeline, known as the Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline is also being considered. If completed, the line will carry 60 mmscmd of gas to be evenly split between India and Pakistan. Another pipeline being discussed is the India-Bangladesh–Myanmar gas pipeline. This gas is currently being evacuated to China. But with China already getting cheaper gas from Russia, it will let go of the rights of buying this gas from Myanmar. None of these projects at present are beyond the feasibility stage and hence it is very difficult for any of these projects to make significant contribution by 2025 to turn India into a gas-based economy.

Key recommendations

Government policy

India is a regulated gas market wherein the government controls the supply and pricing of domestically produced gas along with the majority of infrastructure.

Little has been done to promote the gas market as the focus is on renewable energy now, and despite gas and renewable being complementary in nature, efforts towards the promotion of gas is found wanting. Policies like mandatory procurement of gas-based power by all distribution companies may be considered. The Central Electricity Authority must provide clear-cut guidelines for meeting peak hour power requirement through gas/LNG. The regulator must formulate policies and guidelines to facilitate the adoption of a long-term sustainable solution in line with the Vision 2030 policy.

The exploration policy up till now has not followed the free market policies and, therefore, it has not been very successful in attracting investments. Many of the blocks were surrendered as investors found them to be of marginal/low returns. A welcome initiative has been the CBM policy, which is very much in sync with the market; the same needs to be replicated in other policies.

The PNGRB must ensure the following to enable a gas-based economy:

- Before tendering for any of the pipeline, the PNGRB must get all approvals like right of way (RoW), environment and other applicable clearances for the construction of pipeline. This will de-risk the infrastructure companies and will ensure better participation.

- A pipeline operator must be guaranteed a certain level of return on his investment and in case the utilisation falls below the considered utilisation, the PNGRB must develop a mechanism to support the operator. This, in turn, will ensure the connection of an undeveloped market with future potential to the gas grid.

- A viability gap funding must be provided for all such routes where the pipeline utilisation is expected to be low. This, in turn, will allow for market development and, therefore, pipeline projects will attain commercial sustainability in the future. Infrastructure status has to be provided to gas pipelines as this will facilitate lending and make projects more lucrative.

- The PNGRB must come up with a PPP model for setting up an NGG as direct participation by the government acts as a great enabler for any project. All major project tendering must be planned along with the requisite approvals and then awarded on a PPP model so that we can ensure their timely completion. Three terminals, Kochi, Mundra and Ennore, are suffering because of an incomplete pipeline.

- The government in order to facilitate infrastructure and market development may work towards building critical pipeline connecting markets (as proposed in gas highways).

- The national grid may use the routes in use by the national highways and Indian Railways, which have deep penetration all across India.

A comparison of the national highways and Indian Railways, which has a wider reach across India with the gas pipeline infrastructure, indicates that gas is very far from reaching the homes of all Indian citizens. The following suggestions should be considered by policymakers to speed up the laying of pipelines:

- While sanctioning all new roads and railway tracks (including RoW), provisions should be made for setting up a gas pipeline and, if possible, they should be simultaneously awarded as that would reduce the execution cost.

- While deciding on new routes for making inroads into new markets, road and railway routes may be explored wherever possible to utilise the already laid infrastructure.

Gas pricing

As we move ahead towards a gas-based economy, India must go towards a free market economy and any assistance provided to industries earlier through distorted pricing and allocation must be covered not by distorting the market but by providing direct incentive to the end-consumers (as is being done in LPG – Direct Benefit Transfer). This will allow the gas market to develop and, improve efficiencies and economies of scale, which will hugely benefit the end consumer. The government must work towards policies, enabling free market and fiscal stability with minimal regulation to attract investment.

If the pricing and allocation regulation is removed, LNG importers will have the flexibility to supply without constraint, allowing new companies to supply. This approach by the government will infuse new investment, which is required for transitioning to a gas-based economy.

Unbundling of Gas Transportation & Marketing companies

GAIL owns around 70 per cent of the pipeline network in India and markets the majority of the gas consumed in India. To have a free gas market, the marketing companies should have transportation infrastructure as this will enable them to keep competition out of the market by denying access to customer. Today, GSPC and GAIL have monopoly over gas marketing as they control the majority of infrastructure and this slows down market development and inefficiency. Unbundling will provide accountability to the transportation company, allowing them to concentrate on the gas transportation business.

It has already been proposed that such companies must be unbundled, making transportation and gas marketing as separate companies each responsible for its own balance sheet. This, in turn, will lead to better operational efficiency. Although this has been discussed and agreed in principle but actions leading to unbundling still have many challenges to overcome.

India-specific gas hub

As India aspires to move to a gas-based economy, it is imperative that an India-specific gas hub be developed wherein buyers and sellers are free to trade with each other without any third-party intervention as long as they abide by the free market trading rules set by the regulator. A good hub must have the following pre-requisites:

- Demand-supply gap

- Good number of buyers and sellers trading significant volumes

- Infrastructure to support the physical flow of gas from seller to buyer

- Bringing gas under GST.

- No market distorting regulation

- Autonomous administrative bodies – one working for physical volume contract settlement and the other working for commercial contract completion within the framework prescribed by the regulator.

For the success of the hub, it is imperative that the government and the regulator assume the following roles:

- The government moves from being a market participant (as the owner of gas or pipeline assets) to a market oversight authority by empowering the PNGRB

- The PNGRB establishes market rules to ensure fair trading, and open access of pipeline storage and re-gasification

- The regulator monitors market behaviour to eliminate or preclude any manipulation.

- A successful operating gas hub will do wonders to India’s dream of transitioning to a gas-based economy as it will attract investments for pipeline infrastructure, LNG import terminals, CGD networks, spot/short-term LNG sales and the transnational gas pipeline.

The road ahead – A gas-based economy

The government must concentrate on integrated gas infrastructure planning and execution, taking key policy initiatives, forming a robust regulatory framework and ensuring stable fiscal policy to promote and support investment and drive growth to ensure a free market for gas.